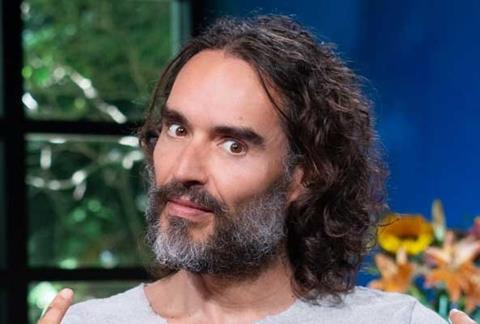

Russell Brand reportedly asked the evangelist J. John for help in examining his newfound Christian faith. But when a photo emerged of Brand standing alongside Christian leaders, it prompted a huge online backlash from those who feared that serious allegations regarding Brand’s treatment of women were being minimised. Can a Christian desire to welcome all, unintentionally give abusers a free pass?

You may have noticed that Russell Brand has recently become a Christian.

The long-haired lothario’s rambling videos and social media posts have become undeniably Jesus-inflected. He’s been baptised in the Thames by another celebrity believer, the adventurer Bear Grylls. He’s posted photos of himself – clad only in white underpants – baptising others in rivers. His Instagram feed regularly features him praying and sharing thoughts from the Bible. He even ended a recent live interview with the former Fox News host Tucker Carlson by leading the hundreds-strong audience in the Lord’s Prayer.

My life has changed. Praise Jesus. pic.twitter.com/E7ePECmrqR

— Russell Brand (@rustyrockets) September 6, 2024

No ordinary convert

Ordinarily, this unexpected turn of events would be cause for celebration across the Church. But Brand is no ordinary celebrity convert. Brand is controversial with a capital C. He first hit the limelight as a brash and loquacious TV host and comedian, but was fired from his BBC radio show after leaving voicemails on air to the actor Andrew Sachs, bragging about sleeping with his granddaughter. After a brief stint as a Hollywood movie star and equally brief marriage to popstar Katy Perry, he has built up a huge following as a wellness guru/right-wing provocateur/online influencer. He revels in his scathing contempt for authority figures. One recent online post, interspersed among the Bible verses, saw him cackling over a video of the far-right conspiracy theorist Alex Jones confronting the respected Christian scientist Francis Collins (who was deeply involved in America’s covid vaccine programme), accusing him of being a worse murderer than Hitler. Brand’s YouTube channel – which boasts over six million subscribers – fulminates against Big Pharma and the biased mainstream media and sells £71 pseudoscience stickers which supposedly ‘protect’ you from entirely non-harmful electro-magnetic radiation.

Just over a year ago, a Channel 4 and Sunday Times investigation published testimony from four women who accused the comedian and actor of rape and sexual assault. Brand strongly denied the allegations, but two police forces have confirmed they are investigating the claims and said several new alleged victims have also come forward following the documentary. It was a few months after this – after he had been dropped by his publisher and agent and his content scrubbed from BBC iPlayer – that he found Christ.

The photo

A lot of believers, including some high-profile church figures, have shown no hesitation in welcoming Brand’s conversion to Christ. J John, the well-known evangelist, has been meeting with Brand for a weekly Zoom Bible study for months and has also had the star and his family round to his house several times. “His conversion to Christ is genuine and ‘heaven and earth rejoice over every new believer’,” he told Premier Christianity. In fact, John said he had been prompted by God to pray for Brand for years, despite having never met him. But he insisted none of this was special treatment: “It’s not because Russell Brand’s a celebrity, it’s anybody; anyone who wants to progress in their journey of faith, I will endeavour to do what I can to help them.” So when Brand asked John for help in piecing together his new faith, the evangelist set up the weekly Bible studies.

But when John invited his new friend to an annual retreat he runs at his home for evangelists, the backlash was strong. A photo of the 15 men, Brand at the centre, was posted on the evangelist’s Instagram page, prompting howls of outrage and shock from many.

Didn’t these grinning evangelists know they had their arms round the shoulders of a serially accused rapist, let alone an anti-vax conspiracy theorist? How could they be so dazzled by his dubious celebrity to platform someone under investigation for serious sexual offences?

Natalie Collins, a Christian gender justice activist and writer, said she had been inundated by messages from women horrified by the Instagram post. Did any of the evangelists in the photo really think through the implications of what Brand is accused of, she wondered. “How many of them would be happy for him to spend time alone with their daughters?” The responses from those pictured varied widely. One, Matt Summerfield, posted a lengthy statement online apologising for his “problematic, confusing, triggering and painful” participation in the now infamous photo. “I can see how this situation has called into question my commitment to advocate for women,” he wrote.

Several others involved quietly deleted their Instagram comments in hopes the controversy would blow over, but a few have robustly defended the incident. Greg Downes, another of those on the retreat, reiterated in a statement online that Brand was “innocent until proven guilty” and the photo did not mean he necessarily endorsed everything the comedian had ever done or said. Jesus was a “friend of sinners”, he added, before quoting words from Desmond Tutu: “When it came to who Jesus chose to keep company with – his standards were really quite low.”

Justice and mercy

The incident has crystallised a longstanding bone of contention within the Church: how should we respond when someone who is accused of horrible crimes comes to faith? We all believe that no sin is beyond the forgiveness offered at the cross, but does that require public repentance and contrition first? How does our gospel of grace intersect with a worldly criminal justice system? Can our desire to welcome anyone unintentionally give abusers a free pass?

Everyone, even Brand’s most vociferous critics, agrees nobody is beyond salvation (even if some quietly question whether his high-profile conversion is a PR stunt to distract from the police inquiries). But what about prominent Christian leaders getting alongside him to encourage and disciple? Is that wise?

John has no time for those who question why he is so involved, echoing Downes’ line about Jesus being a “friend of sinners”. “We all have baggage, I’ve got baggage. Did Jesus say to the disciples when he called them ‘Oh, you got too much baggage, and you’ve really hurt a lot of people, so I’m not going to let you be in my Bible study group’?” As an evangelist, introducing people to Jesus was what he did, John added. “I believe in being born again. Do we not believe in redemption? What kind of a gospel are we communicating to people?” Likewise, Downes said his life’s work would be worthless if God could not take “sinful, immature and broken” people like Brand and empower them through the Holy Spirit to change.

Collins said she had no issue with Downes or John trying to help Brand develop in his new faith. What she struggled with was a refusal to take seriously the allegations against him. Despite the absence of criminal charges, let alone a conviction in court, safeguarding meant making judgements about risk, not getting tied up in knots about innocence or guilt. To lapse back on lines like “we’re all fallen” and “innocent until proven guilty” was to “privilege those who have caused harm while neglecting those who have been harmed”. Far too often she had seen churches so keen to live out a gospel of scandalous grace that men who abuse and harm women had been swiftly forgiven and reintegrated into leadership, while their victims were left ignored and forgotten. “Our theology of grace has to reckon with the harm of sin, it’s not a cover-all” she argued. Even if nobody’s past disqualified them from heaven, it might be right to disqualify them from leadership and prominence in the church, said Collins. Those engaging with Brand and giving this very new believer an uncritical platform in the church needed to think through whether they were being manipulated and how they could safeguard others.

When pressed on this point, John said not everyone who is investigated by the police turns out to be guilty, citing the example of his friend Cliff Richard. “Maybe when the investigation is finished we can have a different conversation… if there is anything he has to do to make restitution. I pray and hope he will, like Zacchaeus did. But in the meantime let’s not be brutal in our judgment of people like him. Why are we so angry, so judgemental? Why do people want vengeance?” Several times, John returned to Jesus’s words in Matthew’s gospel: “Do not judge, or you too will be judged.” The evangelist said he did not want to minimise the pain some may have experienced from Brand, but recalled an incident in his childhood when he’d been accidentally injured while playing a game at the Scouts, and needed stitches. “I still have the scars. Shall I complain? That must have been when I was 12, I’m now 66. Shall I now sue the Scouts for the trauma that they caused, or should I just get over it and move on?” When asked if he meant people need to “get over” whatever Brand may have done in the past, the evangelist replied, “No, no. [What] I’m trying to say is…Jesus encourages us to pray the Lord’s Prayer – ‘forgive us our sins, as we forgive those who sin against us.’ How am I going to practice that today with everyone that’s hurt me? I’ve been hurt, I’ve received abuse from church leaders, how do I respond to that?…Because if I keep unforgiveness in my heart it’s toxic…Helping people to forgive is the heart of the Christian message.”

Russell Brand needs people in his life who are more interested in him developing the fruits of the Spirit than his fame

But others, including Collins, feel this too quickly wipes away the harm Brand may have caused, which he does not yet seem to be reckoning with. “Becoming a Christian does not give us a free pass from accountability, it involves me making amends, taking action,” she said. She worried John and others who are mentoring Brand were getting “excited about their proximity to fame”, which was why they had “lost all their ability to critically think about the implications of having a photograph on the internet with that man”. The Instagram post did not speak to her of a group of mature believers discipling a new convert. Given Brand’s ultra-high profile life filled with controversy and exhibitionism, the right kind of discipleship for Brand should be happening invisibly behind closed doors, she argued, not on social media. “Russell Brand needs people in his life who are more interested in him developing the fruits of the Spirit than his fame.”

But John strongly denied he was dazzled by Brand’s celebrity, insisting he was similarly discipling many others, of whom only some were “very high profile”. He often invited guests to his annual retreat for evangelists so they could soak up the wisdom in the room and be encouraged in their faith. “There were no mixed motives about it. I asked him to come as a spectator, to hear the conversation that we’re having, to encourage him in his journey of faith. That’s all it was. He left after two hours.” Does he regret posting the now infamous photo? “I flipping do! I just didn’t imagine it. The church arena is so hostile. All I want to do is introduce people to Jesus.”

9 Readers' comments